The Science of Reach: How Poor Vehicle Layouts Increase Fatigue and Injury

Jan 4, 2026

Most discussions about vehicle fitouts focus on storage capacity, payload, or how much gear can be carried. Far fewer consider how often a technician has to reach, bend, twist, or climb during a typical day.

Yet these movements, repeated hundreds of times per shift, play a major role in fatigue, musculoskeletal strain, and long-term injury risk. This is where the science of reach comes in.

Reach is not just about whether something is technically accessible. It is about how far the body must extend, how often it must do so, and what posture is required to complete everyday tasks. In fleet vehicles, poor reach design quietly increases physical load on operators, even when the fitout looks organised and compliant on paper.

Understanding reach is essential for designing safer, more productive fleet fitouts.

What Is “Reach” in a Vehicle Fitout Context?

Reach refers to the distance and body movement required for an operator to access tools, parts, consumables, and equipment inside a vehicle.

In practical terms, it includes:

- Horizontal reach into shelving or drawers

- Vertical reach above shoulder height or below knee height

- Reaching while twisting, leaning, or stepping up

- Reaching while carrying weight

Every time a technician stretches to retrieve an item, the body absorbs load through the shoulders, spine, hips, and knees. Individually these movements feel minor. Over a full workday, and across years of vehicle use, they add up.

Why Reach Matters More Than You Think

Poor reach design rarely causes immediate injury. Instead, it contributes to cumulative fatigue and repetitive strain.

Common outcomes include:

- Shoulder and rotator cuff strain from repeated overhead reaching

- Lower back pain from forward flexion and twisting

- Knee and hip stress from stepping in and out of vehicles

- Reduced grip strength and control when reaching at full extension

- Faster onset of fatigue, especially late in the day

For fleets, this translates into increased injury risk, reduced productivity, higher workers compensation exposure, and lower job satisfaction.

The Biomechanics Behind Reach and Fatigue

From a biomechanical perspective, the body is strongest and most stable when joints operate close to their neutral range. As reach distance increases, muscle effort rises sharply.

Key principles include:

- The further the reach, the greater the load on the shoulder and spine

- Reaching above shoulder height reduces strength and control

- Twisting while reaching significantly increases spinal load

- Fatigue reduces postural stability, increasing injury risk later in the day

In vehicle fitouts, these risks are amplified by confined spaces, uneven footing, and the need to work quickly under time pressure.

Common Layout Mistakes That Increase Physical Strain

Many reach-related issues come from well-intentioned but poorly considered design choices.

Deep Shelving

Deep shelves often look efficient because they maximise storage volume. In practice, items at the back require extended reach, leaning, and loss of balance, especially when accessed from ground level.

Overhead Storage Overuse

Placing frequently used items above shoulder height forces repeated overhead reaching. This is one of the most common contributors to shoulder fatigue and strain.

Floor-Level Storage for Heavy Items

Storing heavy tools or parts on the floor or low shelves increases bending and lifting demands, placing stress on the lower back.

Poor Zoning of Equipment

When commonly paired tools are stored far apart, technicians are forced into unnecessary movement, twisting, and repeated reaching.

Access from a Single Door

Layouts that require accessing multiple zones from one entry point increase step-ups, reaches across the body, and awkward postures.

How Fatigue Increases Injury Risk Over Time

Fatigue changes how the body moves.

As muscles tire:

- Posture becomes less stable

- Movements become less controlled

- Reaction time slows

- Small balance errors become more likely

This means a layout that feels manageable early in the day may become hazardous by mid-afternoon. Fatigue also increases the likelihood of slips, trips, and dropped objects, particularly when reaching at height or depth.

For fleet vehicles used daily, this is a compounding risk.

Designing for the “Primary Reach Zone”

Good fitout design prioritises what ergonomists call the primary reach zone. This is the area where items can be accessed comfortably without excessive stretching, bending, or twisting.

In a vehicle context, this generally means:

- Between mid-thigh and chest height

- Within arm’s length without leaning

- Accessible with both feet stable on the ground or vehicle floor

Frequently used tools, parts, and consumables should live in this zone wherever possible. Less frequently used items can be placed outside it, but should still be accessible safely.

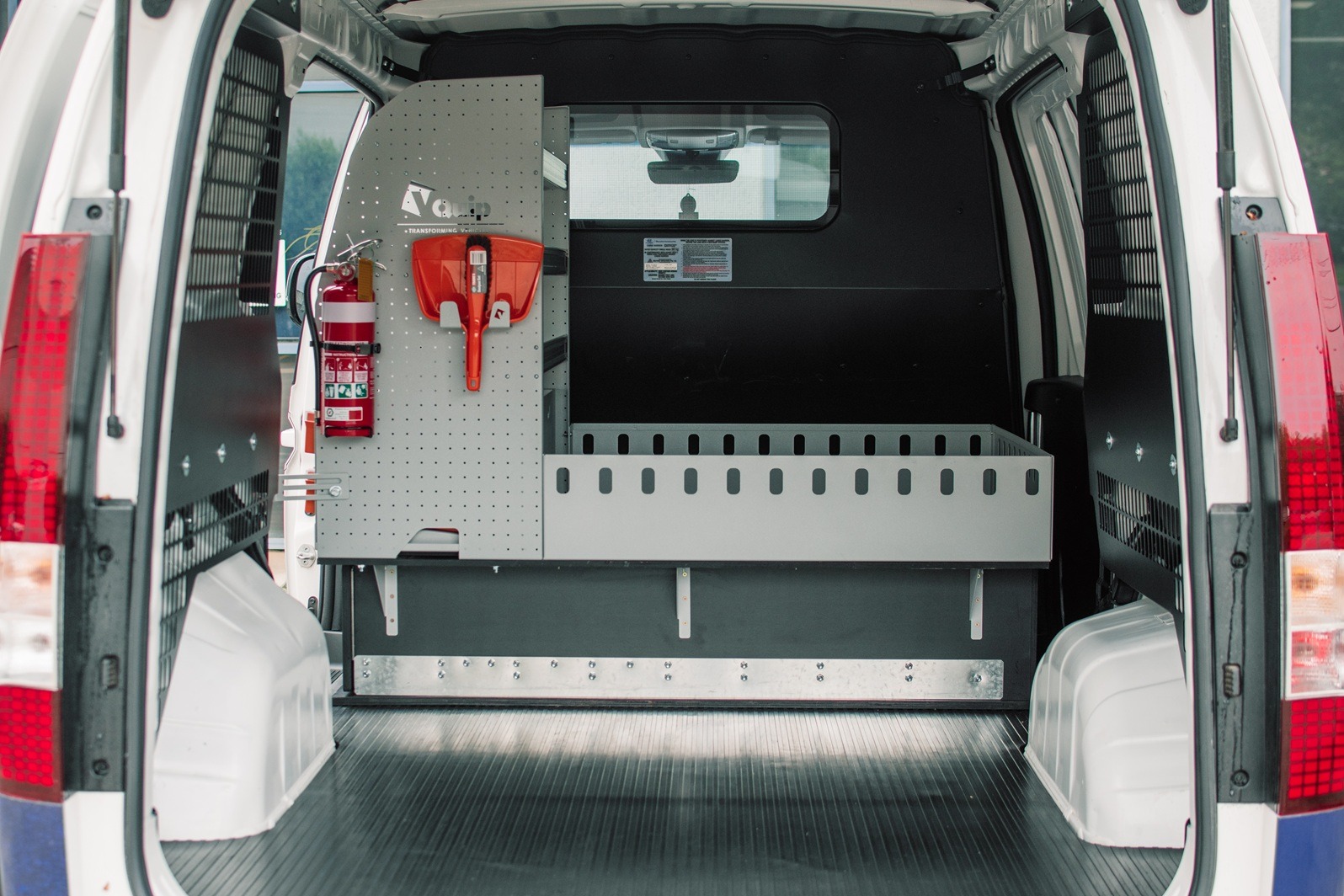

The Role of Drawers, Slide-Outs, and Modular Systems

Modern fitout systems can dramatically reduce reach strain when used correctly.

Drawer Systems

Drawers bring contents to the operator rather than forcing the operator to reach in. This reduces shoulder extension and improves visibility and control.

Slide-Out Trays and Benches

Slide-out benches and trays allow heavier equipment to be accessed at waist height, minimising bending and lifting.

Modular Layouts

Modular systems allow layouts to be tuned to specific roles, ensuring high-use items stay within the optimal reach zone.

The key is not simply adding these features, but positioning them based on task frequency and operator movement patterns.

Why Operator Input Matters

No one understands reach demands better than the people using the vehicle every day.

Engaging technicians during the design phase helps identify:

- Which tools are used most often

- Where fatigue builds up during the day

- Which movements feel awkward or unsafe

- How workflows actually occur on site

Designing without this input often results in layouts that look efficient but feel physically demanding in real use.

Reach, Productivity, and Consistency Across Fleets

Poor reach design does not just affect safety. It also impacts productivity.

Every extra reach, step, or adjustment adds time. Across a fleet, these small inefficiencies multiply into meaningful productivity losses.

Consistent, well-designed layouts also reduce cognitive load. When every vehicle is laid out logically, technicians spend less time searching, repositioning, or compensating for poor access.

This consistency supports faster onboarding, safer behaviour, and more predictable performance across the fleet.

Designing Vehicles That Work With the Human Body

The science of reach reinforces a simple truth. Vehicles should be designed around how people move, not just how much they can carry.

A fitout that reduces excessive reaching:

- Lowers fatigue

- Reduces injury risk

- Improves task efficiency

- Supports long-term workforce health

For fleet managers, reach is not a minor ergonomic detail. It is a core design consideration with real safety, productivity, and cost implications.

At VQuip, we design vehicle fitouts that respect how people work inside them every day, not just how they look at handover.